ANTONIO PIPPO PEDRAGOSA, Periodista, Escritor, Editorialista. Director Gral. de Cultura Tanguera para Diario Uruguay.

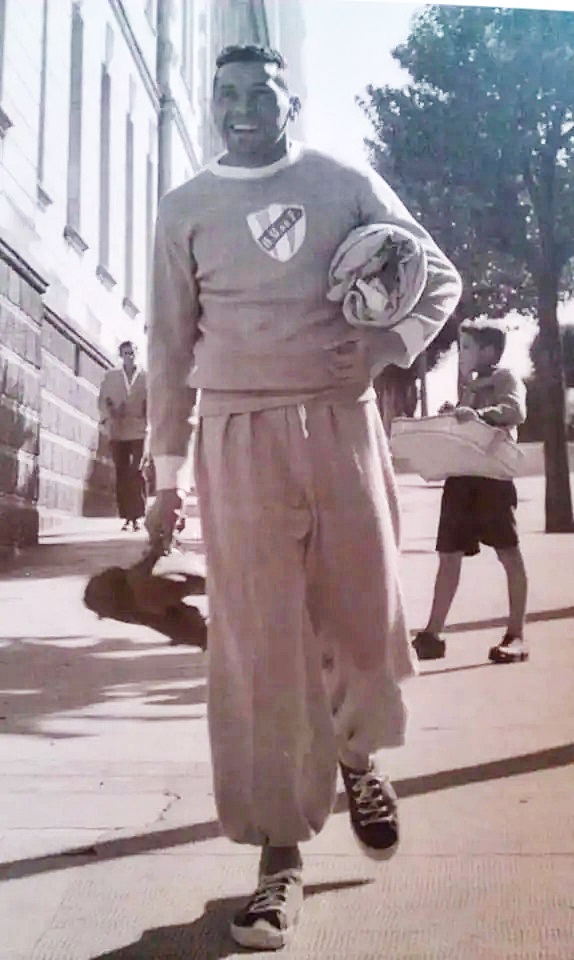

Obdulio Jacinto Varela fue el máximo ídolo del fútbol uruguayo. Una personalidad atrapante, contradictoria, que dejó una huella imborrable en el deporte, sobre todo después de capitanear el equipo nacional que ganó la Copa del Mundo de 1950, derrotando ante 200.000 personas, en Maracaná, al locatario Brasil.

Obdulio Jacinto Varela was the greatest idol of Uruguayan football. A captivating, contradictory personality, who left an indelible mark on sport, especially after captaining the national team that won the 1950 World Cup, defeating host Brazil in front of 200,000 people at Maracaná.

Sobre él -en vida y en familia- escribí mi primer libro, a los cincuenta años: una biografía novelada de este hombre que describió no sólo su imagen, y la de su inolvidable esposa Catalina Keppel, sino de una forma de ser, de cómo se puede ser un señor tanto en la desventura como en el aplauso, que es también una forma de vivir que perdura en los bajos de la sociedad. En aquellos años y ahora. Lo resumo en el epílogo, al que titulé atrevidamente “Pelota afuera”.

About him – in life and as a family – I wrote my first book, at the age of fifty: a fictionalized biography of this man that described not only his image, and that of his unforgettable wife Catalina Keppel, but of a way of being, of how You can be a gentleman both in misfortune and in applause, which is also a way of living that endures in the underbelly of society. In those years and now. I summarize it in the epilogue, which I boldly titled “Ball Out.”

PELOTA AFUERA

BALL OUT

Ha quedado escrito por ahí, no sé bien dónde, que no hay vida posible sin contradicciones.

It has been written somewhere, I don’t know where, that there is no possible life without contradictions.

Le han dicho ídolo y no es cierto. Le han hablado de su gloria y no existe. Han ido a tocarlo, a ver cómo es y siempre les resultó una cosa extraña, distante, incomprensible e incomprendida. Un hombre, sólo un hombre, con su montón de virtudes y defectos a cuestas.

They have called him an idol and it is not true. They have told him about his glory and it does not exist. They have gone to touch it, to see what it is like and it always seemed strange, distant, incomprehensible and misunderstood. A man, just a man, with his lot of virtues and defects on his back.

¿Quién nos vendió la fantasía del sueño ideal, que se alcanza por pura voluntad? Ah, no. Fueron otros. Él no se montó encima de epopeya alguna, nos habló siempre de casualidades y nos apaartó cuantas veces pudo.

Who sold us the fantasy of the ideal dream, which is achieved by pure will? Oh no. They were others. He didn’t get involved in any epic, he always talked to us about coincidences and took us away as many times as he could.

Sin embargo, es un símbolo. Un señor melancólico, digno, recostado desde hace años sobre sí mismo y los suyos, que representa una parte muy grande de eso tan eufemístico que llamamos identidad nacional. Alguien suficientemente desprolijo como para ser un clásico. Un tipo -como diría Wimpi- a quien debemos dar gracias, de todos modos, porque el fútbol todavía exista: antes, sí, fue un juego, después, sólo Obdulio Varela impidió que acá se difumase en una invención de la memoria.

However, it is a symbol. A melancholic, dignified gentleman, who for years has leaned on himself and his people, who represents a very large part of that euphemistic thing we call national identity. Someone messy enough to be a classic. A guy – as Wimpi would say – to whom we must thank, in any case, because football still exists: before, yes, it was a game, later, only Obdulio Varela prevented it from being diffused here into an invention of memory.

Hoy está tan hastiado, que sigue contando cada anécdota de dos formas distintas. O tres. Es la modesta diversión que se permite frente a los que, insistentes, violan su ostracismo voluntario, su recogimiento, su cansancio.

Today he is so fed up that he continues telling each anecdote in two different ways. Or three. It is the modest fun that is allowed in the face of those who, insistent, violate their voluntary ostracism, their withdrawal, their fatigue.

Los jugadores de fútbol pueden ganar ahora millones de dólares. En pocos años, con suerte, cambian su vida. ¿O no la cambian tanto? Quizás convenga volver sobre los dichos de Obdulio para intentar una respuesta. Ya se sabe, parte de su peripecia sigue en pie, semejando una caprichosa verdad: ¿cuántos negritos andan por ahí buscando salvarse de la miseria o el delito detrás de una pelota? ¿Cuántos siguen canjeando la escuela o los mandados por una golosina redonda, a la cual se prenden como garrapatas, de día, tarde y noche, con heladas o reventados por el sol?

Football players can now earn millions of dollars. In a few years, hopefully, they will change their lives. Or do they not change it that much? Perhaps it is appropriate to return to Obdulio’s sayings to attempt an answer. You know, part of his adventure still stands, resembling a capricious truth: how many black people are out there looking to save themselves from misery or crime behind a ball? How many continue to exchange school or errands for a round candy, to which they latch on like ticks, day, afternoon and night, in frost or sunburned?

Y aunque ya no habrá triunfos ni multitudes para Obdulio, sino apenas la vejez, la certeza de la muerte, el aburrimiento, su inalterada idea del fútbol le seguirá reivindicando. Algo diferente a lo de hoy.

And although there will no longer be triumphs or crowds for Obdulio, only old age, the certainty of death, boredom, his unaltered idea of football will continue to vindicate him. Something different from today.

Un fútbol tan parecido que conmueve, al antiguo Mercado del Puerto -que él amó- donde la voz del patrón ordena y unos rusos apiñan su ansiedad en el quiosco de tabacos. Y hay dos brasileños que sacan fotos y comen chinchulines. Hombres y mujeres que andan o se cruzan, caminan o se juntan para charlas de ocasión. Alguien, que no encontró lo que buscaba, anda y observa. El cieguito se quedó a tocar “Desde el alma” con su violín desafinado. Aparece un vendedor con sobrantes de ilusiones inventadas. Marineros y oficinistas, parejas arrobadas y paseantes de ocasión, ejecutivos y artistas, nadie falta. Ahí están, emparejadas, todas las edades, razas, gentes. Todos escapando del crepúsculo como si quisiesen ser un incesante manuscrito cotidiano.

A football so similar that it moves, to the old Mercado del Puerto – which he loved – where the boss’s voice orders and some Russians crowd their anxiety in the cigar kiosk. And there are two Brazilians who take photos and eat chinchulines. Men and women who walk or pass each other, walk or get together for occasional talks. Someone, who did not find what they were looking for, goes and observes. The blind man stayed to play “ Desde el alma ” with his out of tune violin. A salesman appears with leftovers of invented illusions. Sailors and office workers, rapt couples and casual strollers, executives and artists, no one is missing. There they are, paired, all ages, races, people. All escaping from the twilight as if they wanted to be an incessant daily manuscript.

Hay que creerlo. Guarda esas imágenes como guarda la vieja camiseta de Wanderers, su amante fiel. Regalará montones de cosas, menos eso. Se le perderán muchísimas otras, ésa no. Son los juegos selectivos de la memoria en el atardecer.

You have to believe it. He keeps those images like he keeps the old Wanderers shirt, his faithful lover. He will give away lots of things, except that. Many others will be lost, not that one. They are the selective memory games in the evening.

Wanderers no porque sí. Y la inclaudicable Catalina Keppel, la húngara, su mujer. Y los vestuarios y el linimento blanco, los zapatos de clavos, la bolsita de agua, la camiseta dura y sudada que se pega y cuesta sacarla. Y el orgullo, el amor propio, las rebeldías, los empecinamientos, las copas buenas y el dinero que sirve si se gasta. Y la pelota, coqueta y sumisa, en la mitad justa de la cancha. Y las noches en a rambla, solo, con la muerte del Mono a cuestas, la amistad de Julio Pérez, “Pata loca”, y hasta aquel abrazo homenaje interminable al narigón Ghiggia, en la final, porque siempre supo que sin él no ganaban. Y los rollitos de billetes escondidos en lugares insólitos que Catalina siempre descubría. Y los dirigentes, que mienten y engañan. Y los periodistas, que cuentan las cosas a su manera e inflaman a la gente con un aire que no existe. Y los hombres de ley, también: el doctor Caritat, el padre de Cata, su propio padre, los niños solos, infectados de una tristeza que no aguanta. Y los enfermos que escuchan el partido por la radio, mirando las descascaradas losas de las paredes de los hospitales. Y los hermanos brasileños, ellos sí, tan nobles, tan agradecidos y con buena memoria. Y mamá, con los negritos chicos al pie de la cama, desarmando ansiosamente el papel de los caramelos, comiendo pollo con las manos y tomando gaseosas por la botella, llenándolo todo de migas y alegría, disfrutando del frío y las estrellas. Y los diarios a repartir: El Día, El Imparcial, El Ideal, La Mañana y El Diario de la Noche. Y los chiquilines por el centro, durmiendo en los bancos o levantando porquerías de las veredas sucias, agarrando moneditas de propina y hartándose al final de mortadela, sorbiéndole los primeros gustos al vino negro y la caña rubia. Y los gritos, las corridas, los juegos. Y los cafés del centro y el sobretodo de Batlle. Y la sonrisa de Gardel, inmensa.

Wanderers not because. And the unwavering Catalina Keppel, the Hungarian, his wife. And the changing rooms and the white liniment, the spiked shoes, the water bag, the hard, sweaty shirt that sticks and is difficult to remove. And the pride, the self-love, the rebellions, the stubbornness, the good drinks and the money that is useful if it is spent. And the ball, flirtatious and submissive, in the right half of the court. And the nights on the rambla, alone, with the death of Mono on his back, the friendship of Julio Pérez, “Pata loca”, and even that endless tribute hug to the big-nosed Ghiggia, in the final, because he always knew that without him they wouldn’t win . And the rolls of bills hidden in unusual places that Catalina always discovered. And the leaders, who lie and deceive. And the journalists, who tell things their own way and inflame people with an air that does not exist. And the men of law, too: Dr. Caritat, Cata’s father, his own father, the alone children, infected with a sadness that cannot be endured. And the sick people who listen to the game on the radio, looking at the peeling tiles from the walls of the hospitals. And the Brazilian brothers, they are so noble, so grateful and with good memories. And mom, with the little black boys at the foot of the bed, anxiously taking apart the candy paper, eating chicken with her hands and drinking soda from the bottle, filling everything with crumbs and joy, enjoying the cold and the stars. And the newspapers to be distributed: El Día, El Imparcial, El Ideal, La Mañana and El Diario de la Noche. And the little kids in the center, sleeping on the benches or picking up rubbish from the dirty sidewalks, grabbing little coins for tips and eventually stuffing themselves with mortadella, sipping the first tastes of black wine and blonde beer. And the screams, the runs, the games. And the cafes in the center and the Batlle coat. And Gardel’s smile, immense.

More Stories

La libertad de prensa en los Estados Unidos en comparación con Uruguay y con países latinoamericanos

AGROTÓXICOS, una discusión necesaria

El hombre serio